Cryo-electron tomography allows new knowledge about poliovirus replication and assembly sites in situ

Published: 2022-12-19

Over the latest three years, the COVID-19 pandemic has had significant effects on global society, economy, and health. Vaccines have mitigated the effects of the pandemic, though COVID-19 disease outbreaks are still common. Global pandemic preparedness efforts are now underway to build capacity to tackle old and new pathogens as well as viruses with the potential to cause a significant threat to public health.

Up until the 20th century, millions of people were affected by Poliomyelitis (polio) annually, and the disease has been known since historic times. Whilst most people infected with poliovirus do not have any symptoms, one in four will exhibit flu-like symptoms, including a sore threat, fever, headache, tiredness, and GI symptoms. In a small number of cases, infection can lead to more severe effects, such as meningitis, or paralysis of the arms or legs. In 1948-1955, before a vaccine was readily available in 1955, several global polio epidemics affected the every day life and life quality of many people, but especially families with children. Parents would avoid crowds, check for symptoms, and avoid public places and sports events. Effective global vaccination campaigns followed, and in 1988 there were only 350,000 cases of polio registered worldwide. Today, polio is uncommon, though there are still confirmed cases in non-endemic countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, and US, as well as outbreaks in polio-endemic areas in Afghanistan and Pakistan. However, polio eradication is proving more challenging than hoped for, as shown by recent detection of poliovirus in London sewage and the first new case in decades of poliomyelitis (i.e. polivirus-caused paralysis) in New York, USA. As part of pandemic preparedness efforts, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently announced it would expand wastewater testing to include poliovirus, not just for New York (NY), but also other cities in the US CDC, 2022.

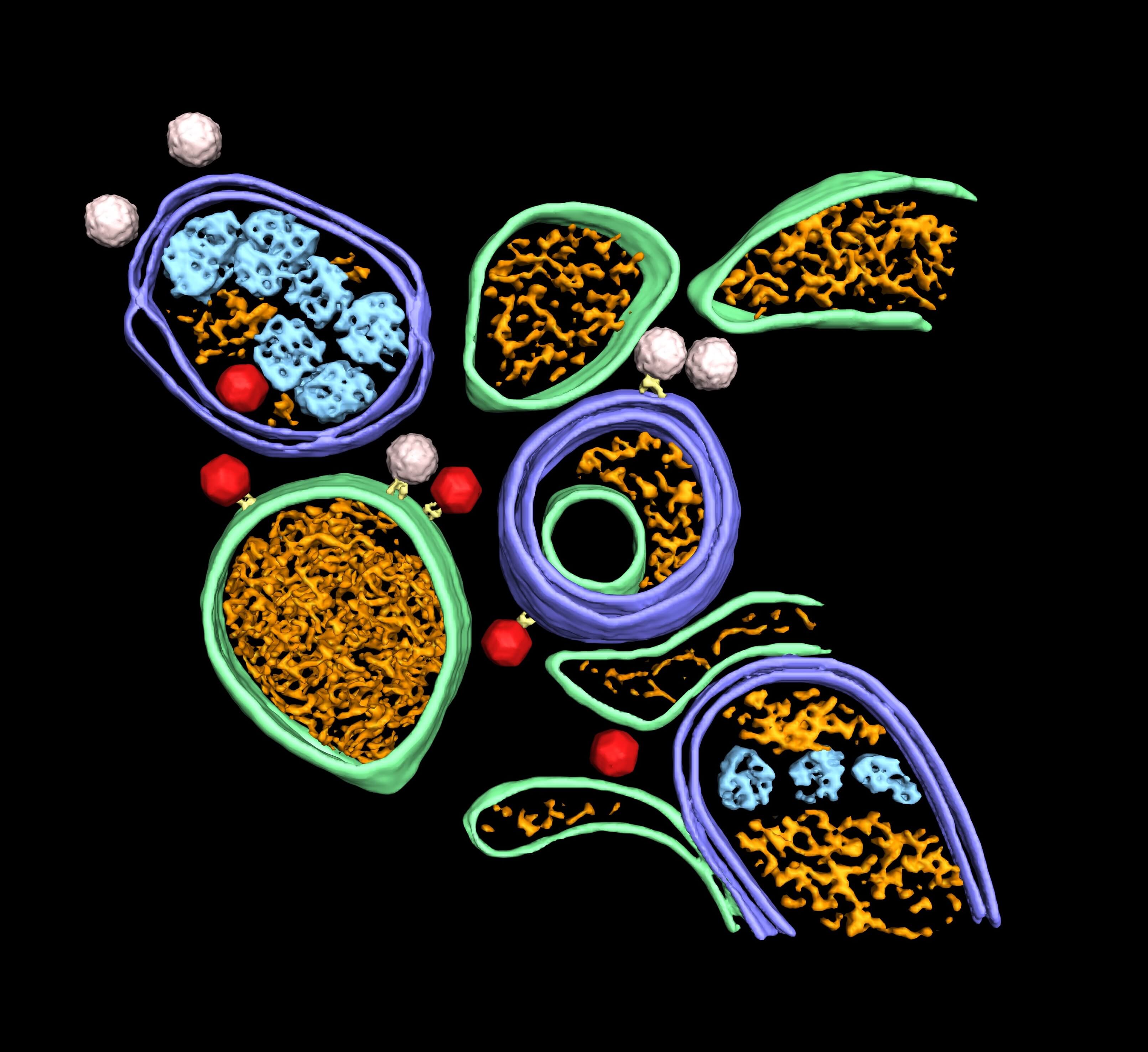

Polio is caused by poliovirus, which is an enterovirus in the Picornaviridae family. Enteroviruses can cause a number of different human diseases, such as poliomyelitis (poliovirus), related acute flaccid myelitis conditions (e.g. EV-D68), and viral myocarditis (Coxsackievirus B3). In brief, the enterovirus particle is a non-enveloped particle (~30 nm diameter), which encapsidates a single-stranded RNA genome of ~7500 nucleotides. Enteroviruses are known to be rapidly multiplied. This is due to remodeling of cytoplasmic membranes for viral genome replication. However, knowledge of how new virions assemble around the newly synthesised genomes and how they are released through secretory autophagy is still warranted. Recent research has shed light on some aspects on enterovirus assembly and release, but key questions have remained unanswered. This is largely due to limitations of the electron microscopy methodology used, which has not allowed visualisation of virus formation inside infected cells.

In a recent article published in Nature Communications, researchers from Umeå University collaborated with colleagues from Stockholm University (SciLifeLab), US, and Australia, used cryo-electron tomography to study how enteroviruses are assembled and packaged into autophagosomes (First author: Selma Dahmane, Umeå University; Corresponding author: Lars-Anders Carlson, Umeå University).

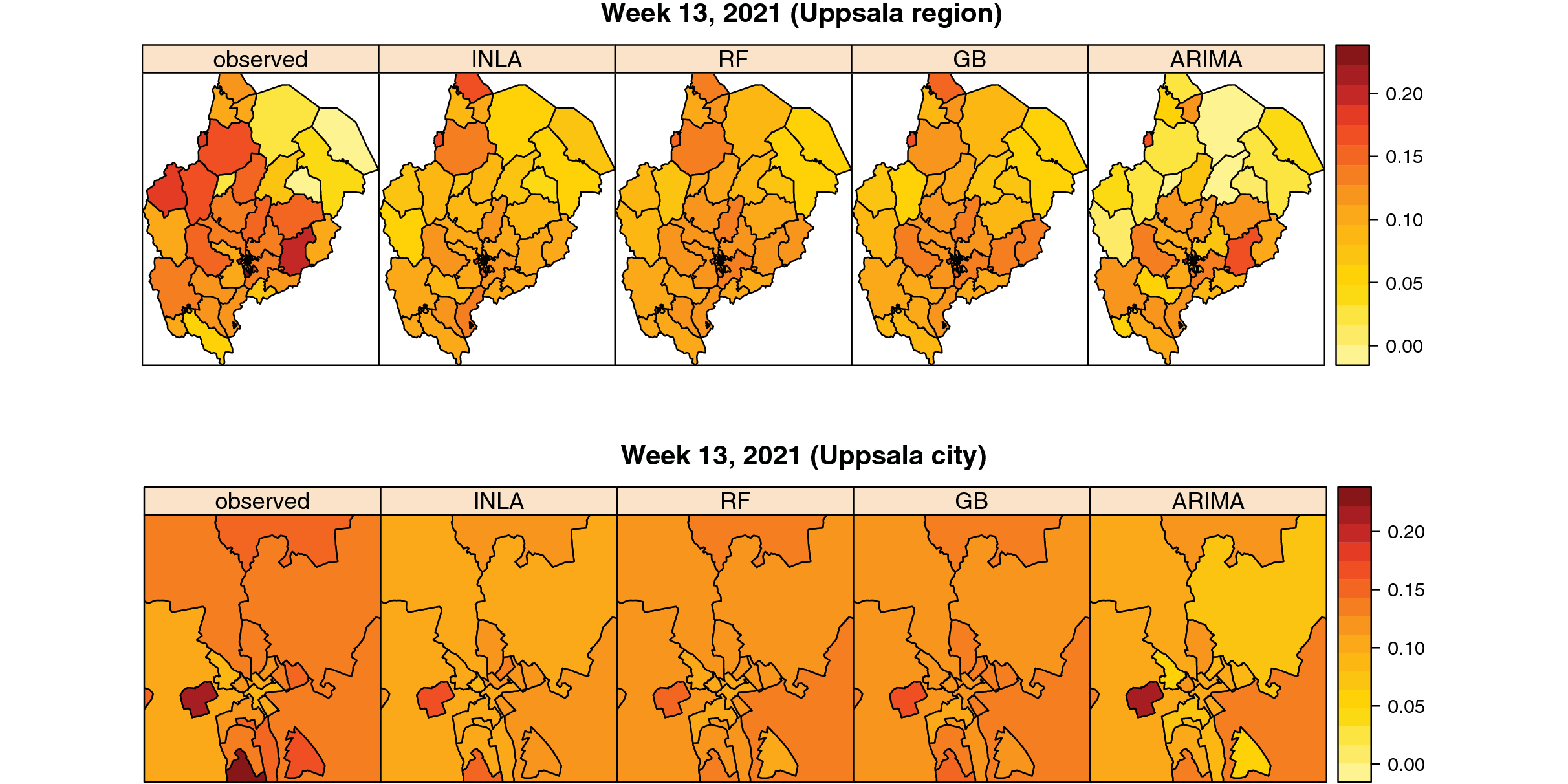

Dahmane and colleagues infected HeLa cells with poliovirus type 1, imaged the cytoplasm with cryo-electron tomography, and followed the process post-infection in order to investigated enterovirus assembly in situ. The tomograms revealed that poliovirus assembles directly on replication membranes. Further, the researchers found that to complete the virus assembly the host lipid kinase VPS34 is necessary. In addition, the researchers showed that the balance between ULK1-induced canonical autophagy and virus-induced proviral autophagy determines the virion production level. Inhibiting the initiation of canonical autophagy, though pharmacological inhibition of ULK1, increased the virion production and release. The poliovirus appears to be able to optimize its environment e.g. by turning off the master switch for canonical autophagy (ULK-1).

In addition, cryo-electron tomograms revealed a multi-layer selectivity in enterovirus-induced autophagy. The autophagy was shown to be able to selectively choose RNA-containing virions over empty capsids, and segregating virions from other types of autophagosome contents. These results have contributed novel insights into the structural framework for multiple stages of the poliovirus life cycle. Future studies to build on this knowledge and further elucidate enterovirus-induced autophagy are warranted and important for pandemic preparedness efforts.

Data and code availability

- The subtomogram average maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession codes EMD-15390 (empty capsid), EMD-15391 (RNA-loaded virion), EMD-15392 (tethered virion), and EMD-13682 (filament). Source data are provided with this paper.

- The script used to pick filament subtomograms from Amira filament tracings is available at GitHub.

Article

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-33483-7

Dahmane, S., Kerviel, A., Morado, D.R., Shankar, K., Ahlman, B., Lazarou, M., Altan-Bonnet, N., Carlson, L.A. (2022). Membrane-assisted assembly and selective secretory autophagy of enteroviruses. Nature Commununications, 13, 5986.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie, the Human Frontier Science Program Career Development Award, and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (through the Wallenberg Centre for Molecular Medicine Umeå).

Read more about the research group at Umeå university/Wallenberg Centre for Molecular Medicine (WCMM) here.